Some Basic Information About Mexico Today

Mexico today has a population of over 111 million people, making it the third most populous nation in the Americas after the United States and Brazil. Of these, about 45 million people constitute the Economically Active Population (PEA). About half of all Mexico’s workers labor in the underground or informal economy for employers who do not pay taxes, do not pay into the national Social Security system (pensions and the national health system), and do not deal with labor unions.

Mexicans earn wages about 1/10 of U.S. workers’ wages

About half of Mexico’s people live in poverty, and about a fifth live in dire poverty. Mexico’s poverty is not simply a result of an historical lag in development. Rather much of this poverty results from the modernization and development programs pushed by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the U.S. and the Mexican government of the last 20 years. Poverty often results from unemployment or from low wages, or wages with declining purchasing power.

Perhaps the most striking symptom of poverty is the declining stature of children. Because of malnutrition, Mexican children in many states in certain age groups have been getting shorter and lighter; that is, seven year olds in 1990 were bigger than seven year olds in 1998. Mexico joined the GATT and NAFTA only to see its population become poorer and its children become stunted.

For seventy years (until 2000) Mexico was ruled by the state-party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The PRI controlled all branches of government as well as the major labor unions (such as the CTM), peasant, and other social organizations of the country. The party has been called a “perfect dictatorship” because with far less violence than other dictatorships, it was able to keep the population under control.

How did this happen? Let’s take a quick look back at Mexico’s history.

Read on to sections covering:

- Mexico before Columbus and Cortez

- Spanish Conquest of Mexico

- Colonial Mexico

- Independent Mexico

- The French Conquest and Occupation

Or if you’re not interested in Mexico’s early history, skip ahead to these sections:

- The Porfiriato

- The Mexican Revolution (1910-1940)

- The Results of the Mexican Revolution

- The Mexican Government Turns Right

- From the Mexican Miracle to the Mexican Mess

- Enter the IMF and the World Bank

- The Mexican Political System

- Years of crisis loosen PRI grip on government

Mexico before Columbus and Cortez

Modern Mexico has a history and culture quite different from that of the United States. Before the arrival of the Europeans, what is today Mexico was inhabited by indigenous people. The indigenous people had immigrated to the Americas by crossing the land bridge across the Bering Straits over 10,000 years ago.

The indigenous people settled in great numbers in Meso-America, that is the region from what is today Panama to about where the city of Zacatecas, Mexico now stands. More than 5,000 years ago they learned to cultivate corn and other foods, and laid the basis for an agricultural civilization. Some historians believe that as many as 25 million people lived in that region when Columbus landed in the Americas in 1492.

The Olmec peoples of the Gulf of Mexico are considered by anthropologists to have been mother culture of Mexico. The most famous Mexican civilizations were those of the Aztecs in central Mexico and the Mayas in the Yucatan Peninsula and southern Mexico. But there were many other important indigenous civilizations — Toltecs, Zapotecs, Tarascans, Purepechas, and many others. Some anthropologists and historians compare these civilizations of Meso-America, including Mexico, to the great civilizations of the Mediterranean.

During the period from 1400 to 1521, the Aztecs, based in the city of Tenochtitlan (the future Mexico City) built an empire based on tribute that extended throughout central Mexico. The Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan is believed to have had a population of 250,000 in 1519, larger than any European city at the time. The Aztecs studied astronomy, practiced irrigation, built great pyramids, temples and cities, and had a written language. Their religion required human sacrifices to please the gods of the sun, rain and warfare, among others.

Spanish Conquest of Mexico

Montezuma II was the head of the Aztec state and empire when the Spanish conqueror Hernan Cortez landed in Mexico in 1519. Cortez and his few hundred soldiers arrived with their sailing ships, horses, war dogs, metal armor, gunpowder and firearms all of which intimidated the indigenous people. (The Aztecs did not have sailing ships, the wheel, metal weapons, or gunpowder and firearms, and there were no horses in the Americas.) Cortez formed alliances with the subject people of the Aztecs, and those subject people provided him with thousands of troops. European diseases to which the natives had no immunity also played an important part in the conquest. Between 1519 and 1521, Cortez succeeded in conquering the Aztecs and then in the next decade he and his men extended their control over most of the other native people.

Colonial Mexico

The conquest of Mexico was followed by colonization by the Spaniards. The conquerors imposed the Spanish government and the Roman Catholic religion on the indigenous peoples of Mexico. Thousands of Spaniards immigrated into Mexico. The Spanish rulers gradually took control of the land, wealth and labor of the country. While the Roman Catholic Church and the Spanish king and queen decided that Indians could not be enslaved, they could be subjugated and forced to work for the Spanish overlords. The Spanish eventually established great haciendas, plantations, ranches, and mines.

The Spanish conquest devastated the indigenous population which dropped from a peak as high as 25 million in 1519 to as little as 2.5 million in 1600. The demographic catastrophe of the indigenous people, whom the Spanish called “Indians,” (indios), led the Spanish to import about 200,000 African slaves. (Over hundreds of years many Spaniards and Indians, and in some areas Africans, inter-mixed, producing the mestizos, perhaps the dominant group in the modern Mexican race.) The Spanish rule of Mexico lasted from 1519 to 1821, that is, for three hundred years.

Independent Mexico

Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, and September 16 has been the national independence day ever since. The first independence movement was led by radical Roman Catholic Priests, father Miguel Hidalgo y Castillo and by Morelos y Pavon. But the radicals were defeated by the Spanish, and independence was eventually won under the leadership of conservative land owners. For most people, Mexico’s independence did not change their lives very much. A Spanish (criollo) elite continued to dominate politics and own the land and mines, while most mixed race people (mestizos) labored as artisans or workers and Indians (indigenas) worked the land for the plantation owners.

Many historians refer to the period between 1821 and the 1860s as the lost half century. During that period a small political elite divided between “Conservatives” and “Liberals” fought for control of the government. Conservatives tended to support the old Spanish system of domination by the Roman Catholic Church, the military and the landlords. Liberals wanted to move to a system of private industry and agriculture more like that in the United States.

Under both Liberals and Conservatives and under generals such as Santa Anna, Mexico suffered a series of devastating and almost catastrophic political and military defeats. Most important, between 1836 and 1854, the United States took more than half of Mexico’s territory, first through the secession of Texas from Mexico, and then through the U.S.-Mexican war of 1847. Most U.S. historians agree that these were unprovoked wars of conquest, driven by U.S. slave states seeking more land for cotton, and U.S. manufacturers in the Northeast looking for markets in the far East.

The French Conquest and Occupation

In the 1860s, the Conservatives invited the French Emperor Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) to come to their aid in their battles with the Liberals. Taking advantage of the Civil War in the United States, which kept the U.S. government from opposing a European invasion of Mexico, Louis Napoleon’s French troops invaded Mexico and established the Austrians Maximilian and Carlotta as the King and Queen of Mexico. The Mexican Liberal Benito Juárez, a Zapotec Indian lawyer and politician, led the Mexican people in their struggle against the Conservatives and the French conquerors.

May 5 (“Cinco de Mayo”) celebrates a Mexican victory over the French at the city of Puebla during those wars, and is a second Mexican Independence Day, though more celebrated among Mexicans in the U.S. than in Mexico. Juárez also carried out a series of reforms, reducing the power of the church and ending protection for Indian groups. This period is known therefore as the period of La Reforma, the reform.

The Porfiriato

In the 1870s Porfirio Díaz became president of Mexico and would be its dictator until the outbreak of the 1910 rebellion. Porfirio Díaz invited foreign capital to invest in Mexico in order to develop and modernize the country. While he attempted to balance British and French investment against U.S. interests, U.S. capital became dominant in Mexico.

Under Díaz, a railroad system was built which connected Mexico City with the port of Veracruz, and with the northern border and the United States. U.S. railroad companies controlled most of the Mexican railroad system. Also under Díaz, U.S. mining companies were invited to invest in Mexico, and the Guggenheims and Rockefeller both moved in. Companies such as Phelps-Dodge and American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) controlled much of Mexico’s minerals. U.S. industrialists such as Edward L. Doheny and later Standard Oil owned much of the Mexican oil industry.

Other U.S. corporations came to dominate in other areas of the Mexican economy. The International Harvester Company controlled the haciendas of the Yucatan which produced henequen or sisal, a fiber used to make twine for the company’s binders. The Wrigley company invested in “chicle” used to make chewing gum. Other U.S. corporations had holdings in rubber and lumber. William Randolph Hearst and other U.S. businessmen bought ranches in northern Mexico.

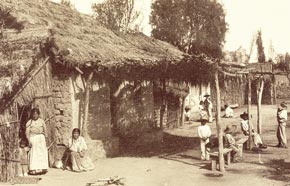

Meanwhile the Mexican landlords’ giant haciendas producing sugar cane or other products for export on the world market encroached on the land of the poor peasantry. Mexican landlords took control of most of the country’s territory, depriving Indians, peasants and small farmers of their land.

Though originally elected as a Liberal, Díaz made peace with and entered into a tacit alliance with the Roman Catholic Church. Díaz kept control of the country through the Federal Army, the “Federales” and through the rural police force or “Rurales.” His slogan was “pan o palo,” bread or the stick. Bread for those who worked with his dictatorship, and the stick to beat those who did not. Under the Díaz regime labor union organizers, peasants demanding land and poor Indians were arrested, tortured and murdered.

Eventually the Díaz dictatorship became identified in the minds of the Mexican people with those forces: Mexican landowners, the Roman Catholic Church, and U.S. and other foreign corporations. Opposition to Díaz and those forces laid the basis for the Mexican Revolution.